The desire for moments of healthy country life is increasing more and more; we are moving towards the “re-ruralization” of cities. During the Renaissance, the city was synonymous with civilization, the countryside with rusticity; leading people out of the countryside and bringing them into the city meant civilizing them. The city was the seat of knowledge, good manners, taste, refinement, the arena in which man fulfilled himself, and yet long before 1800 it had become common to assert that the countryside was more beautiful than the city.

In the nineteenth century, this became a widespread opinion, supported by the material deterioration of the urban environment, which in industrialized England materialized in the mythical London smog. The coal burned at the beginning of the modern era contained twice as much sulfur as is commonly used today; the smoke darkened the air, soiled clothes, ruined curtains, killed flowers and trees, and corroded building facades.

Highly harmful was the pollution caused to rivers by waste materials produced by industries operating in the city center; so much so that since the reign of Richard II, laws against Thames pollution were regularly enacted.

John Graunt in 1965 tells us that overcrowding made London notoriously unhealthy, but many other industrial cities were in little better condition, so it was inevitable that the plague would affect cities more than the countryside, and that the mortality rate would be higher there.

THUS BEGINS THE SPREAD OF THE CONCEPTION OF COUNTRY LIFE, A PLACE WHERE PEOPLE LOVED TO SPEND THEIR WEEKENDS AND SUMMER SEASON, AND WHERE ARISTOCRACY MEMBERS BUILT SPLENDID RESIDENCES.

A trend that is returning. The desire to preserve fields near the city for recreational use partly explains the numerous attempts to prevent the construction of new buildings around London until 1940 when Sir Patrick Abercrombie, a member of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE), proposed and subsequently implemented the plan for Greater London, which imposed a green belt, a zone of respect assigned to agricultural production around the city’s periphery, averaging 11 km wide. Any urban expansion beyond this belt was rejected, and this is the current law known as the Green-Belt.

Religion also played a role in shaping this new taste for country life, described as a more sacred place than the city, and much of the literature of the period displayed what poet John Clare would call the religion of the fields, as St. Francis said, every leaf, every plant, every bush was a page of God’s book, proclaiming its power and goodness.

Many writers explicitly stated that the countryside was created by God, the city by man; in 1928 David Herbert Lawrence, after a period spent in Italy in his travel book called Etruscan Places, wrote: as beautiful as the countryside is, so ignoble is England made by man.

In industrial England, the passion for the countryside was intensified by the enormous development of London, but it was also reinforced by the phenomenon of the city’s deruralization, which became increasingly evident: the reduction in the size of urban gardens and orchards, the disappearance of trees and flowers, and the increase in construction density in response to population pressure.

In Italy, on the other hand, urban life had a very early but harmonious development with nature, so much so that the taste for vacationing (summer retreat in an elegant country villa) first manifested itself in Renaissance Italy, whose true essence lay precisely in recognizing the greatness of the countryside through a competitive action with the city.

Recognizing himself as a transformer of the places he occupied, the Renaissance man perceived the greatness of the surrounding territory without first having to damage it, as happened in England.

Thus not only the city, but also the countryside became the place of transformations, of the ingenious intervention of man who rises as the builder of his places.

It is from such a conception of human intervention that the great architects and urban planners of the Renaissance built villas and gardens, palaces and cities conceived as theatrical stages, and it is from a conception of constructed nature, from an architecture open to the countryside, that the landscape acquires visual dignity, as Lévi-Strauss rightly observed.

These are the values that also guide Walt Disney in the realization of the EPCOT project.

The worship of the countryside, in Italy as in England, did not prevent more and more people from moving to cities, but proportionally as agricultural activities within cities diminished, the idea that the most beautiful city was the one with a more rustic appearance and less cemented urban environment became increasingly widespread.

An example of this thinking is Ebenezer Howard, who in 1902 in Garden Cities of To-morrow declared that city and countryside must marry, thus promoting the ideals of garden cities and green belts; the problem of combining what the city can offer economically and socially with the physical environment of the countryside remains one of the dominant themes of urban planning today.

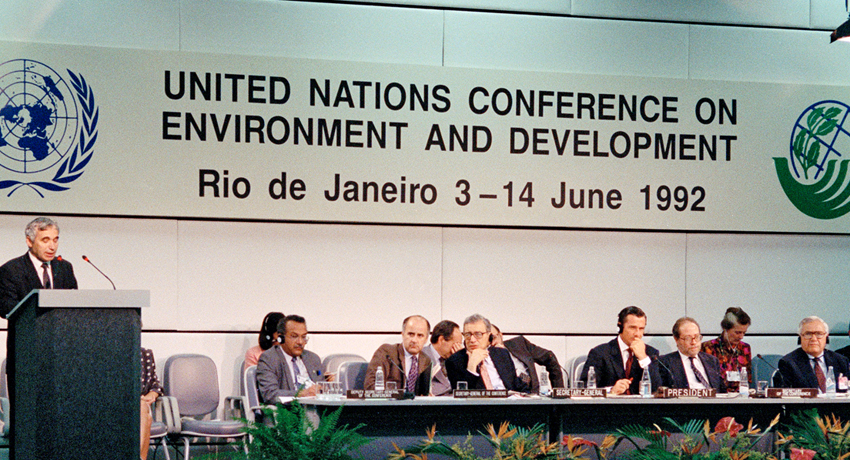

ONLY AFTER WORLD WAR II DID REFLECTION REGARDING GENUINE LIFE AND THE DAMAGE CAUSED BY MAN TO NATURE REACH ITS PEAK, WITH THE CONSEQUENT BIRTH OF ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIOLOGY IN THE UNITED STATES, LATER DEFINED AS AN IMPORTANT REVOLUTION OF FEELING.

Environmental issues and respect for nature are at the center of media agendas in the new millennium; pollution of the food chain, deforestation, the reduction of agricultural areas in favor of industrial uses are now public domain.

A renewed environmental consciousness is stimulating a re-ruralization of cities from below, with the emergence of urban gardens and the rediscovery of traditional farming practices; young people are rediscovering the pleasure of a healthy country life and are increasingly pursuing careers in rural areas, jobs simplified also thanks to the advantages of technological development…

What type of technological development do you think could favor Ebenezer Howard’s dream in the near future, namely celebrating the marriage between Country and City? Can we look to the past to act in the present?