Reflection on Sustainability Between Future and Prosperity

The term “sustainability” is frequently used in various contexts, even though there is still not a full awareness of what it should represent…

The concept of “sustainable development” gained prominence due to the global movement that took place on March 15, 2019, in support of the solitary protest of a sixteen-year-old girl who skipped school every Friday to demonstrate in front of the Swedish parliament against the ongoing climate change. Her name is Greta Thunberg.

The term “sustainable development” was proposed by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, as the guiding principle of environmental policies in the report “Our Common Future” (better known as the Brundtland Report). According to the definition given at that time, development, to be sustainable, must meet the needs of the present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

This definition does not necessarily imply a link between economic development and the environment, although it is entirely reasonable to consider that the relationship between economic development and environmental conditions is the appropriate ground to apply and verify that definition.

Since its introduction, and especially in recent years, policymakers have been repeatedly urged to act in respect of sustainability. Unfortunately, the strong social will to alter current practices is not enough to provide a serious direction for public intervention because the deep ambiguities surrounding the concept of sustainability complicate the choice between alternative policies.

On Wikipedia, we read:

“Sustainability is the characteristic of a process or state that can be maintained at a certain level indefinitely.”

Capital has three components:

- Artificial capital (buildings and infrastructure);

- Human capital (science, knowledge, technology);

- Natural capital (clean air, clean water, biological diversity, etc.).

Based on this general concept of capital, some argue that while the value of the global capital is preserved, one of its components (e.g., natural capital) can be spent, provided that another component (such as artificial capital) is increased by the same measure. This view is called weak sustainability and is frequently (and conveniently) adhered to by many politicians and businessmen in the name of progress.

Advocates of so-called strong sustainability argue instead that natural capital should not be further depleted because the consequences could be irreversible (desertification, diseases, climate change), and that the long-term impact on human life and biodiversity is a major unknown. The vast majority of scientists and ecologists support this latter view, but the debate remains open.

A proponent of the “weak” philosophy is Howarth, who interprets the constraint of non-decreasing utility as a principle that ensures future generations the opportunity to enjoy at least the same quality of life as the current generation, understanding sustainability as the condition that ensures that the expected utility of agents does not decrease over time.

The “strong” philosophy, instead, places particular emphasis on the problem of uncertainty surrounding environmental issues and the irreversibility of some processes of depletion of natural resources. Suggestions from this school of thought take the form of “precautionary principles” according to which it is necessary to safeguard natural heritage in the present against possible catastrophic effects in the future.

IN PRACTICE, THE PROBLEM IS THAT THE CONCEPT OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT HAS BEEN INTERPRETED IN A VAGUE MANNER, BUT IT IS NOT VAGUE.

ITS FAULT LIES IN BEING BOTH APPEALING AND CHALLENGING AT THE SAME TIME.

TOO APPEALING TO BE PUBLICLY REJECTED, TOO TOUGH TO BE FULLY IMPLEMENTED. THE STAKE IS NOTHING BUT THE DEVELOPMENT MODEL OF MARKET ECONOMIES, BASED ON THE UNLIMITED GROWTH OF CONSUMPTION, WHICH IS NEITHER ECOLOGICALLY NOR SOCIALLY SUSTAINABLE.

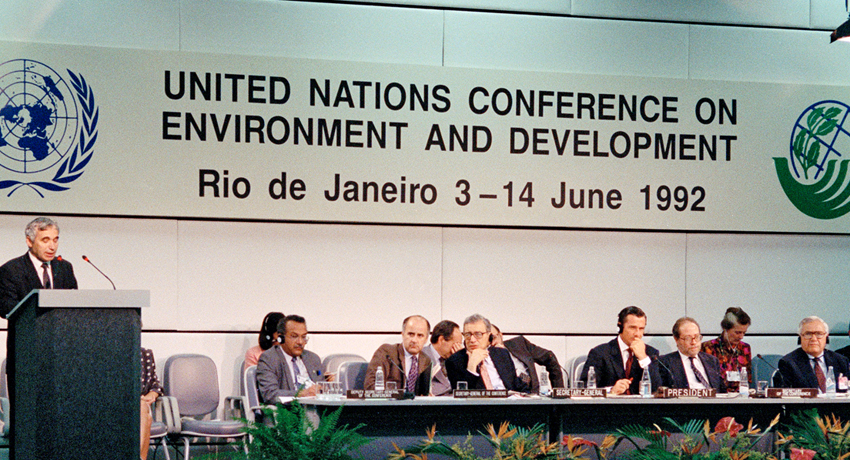

A new development model is needed that questions lifestyles, especially in rich countries. This is what was indicated in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro based on the interpretation that the Brundtland Commission gave to the concept of sustainable development.

That this indication is not vague at all, but on the contrary strong and meaningful, is demonstrated by the political premise with which the President of the United States, George Bush Senior, presented himself in Rio de Janeiro: “Our way of life cannot be subject to negotiation.” In Europe and other Western countries, the approach is certainly less assertive than the American one, but perhaps also less clear. There is not a full awareness of the stakes (or at least it is not explicitly stated), and therefore there is never a coherent and definitive choice in favor of or against the idea of ecological and social sustainability.

A concrete example of unsustainability is the management of waste disposal in Italy: instead of reducing waste upstream and incentivizing and concretely implementing nationwide waste sorting, the focus remains on building and filling landfills and constructing new waste incinerators, two complementary and not mutually exclusive solutions as their promoters would have us believe.

A renewed awareness of the concept of strong sustainability is spreading across our country, in the form of protests and demonstrations mainly driven by the evidence that the development model imposed globally, in the form of “lifestyles” aimed at rampant consumerism promoted by an increasingly international cultural industry, is undermining the foundations of potential sustainable development at the local level, is seeking to irreversibly transform the land use of our territories rich in characteristics from which cultures derive that are somewhat “old” but should not be discarded for this reason, rather they should be recycled or better reused.

So, the watchword is glocal, increase knowledge of the different and maintain the specificities of territories and cultures for a global awareness of local characteristics.

Sustainable development is understood somewhat as the pursuit of prosperity, but not in the consumptive sense and with planned obsolescence of the “progress” that is presented to us, but rather in the sense of widespread well-being in a production chain inserted in a context of informed and responsible consumers.

What meaning, then, do we attribute to the concept of sustainability?

Innovation in production processes in the agricultural sector can contribute to responsible exploitation and sustainable development of our countryside, thereby promoting the sustainability of our cities in return.

Perhaps sustainability should be sought precisely in agricultural and rural areas rather than in cities, which by natural evolution are unsustainable. Reduce consumption primarily of land, water, and air, the resources that have allowed and continue to allow life on earth.